The chairman of a Commons committee which has led an inquiry

into crime figures accused Home Office ministers of “complacency” after they

trumpeted yesterday’s figures as a success for the government.

|

| Bernard Jenkin MP |

Bernard Jenkin MP, chairman of the public administration

select committee said: “I am disappointed about the apparent complacency shown

in some of the comments being made about today’s release of crime statistics. It

is as though there were no concerns at all about the reliability of the police

recorded crime statistics, let alone that they have been officially downgraded

by the statistics watchdog. It is this kind of complacency which has led to the

unreliability and downgrading in the first place – and this complacency goes

right up to Home Office ministers.”

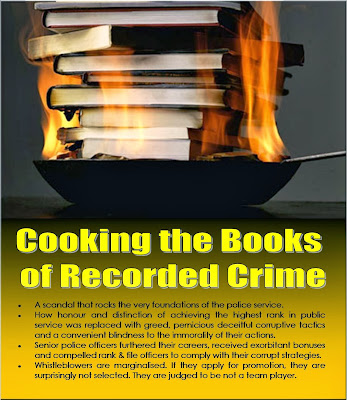

Last November the committee was told by serving and retired

officers that official crime figures are skewed by the police - often at the

instruction of senior officers - to make their performance appear far better

than it is in reality.

In response the UK Statistics Authority stepped in last week

to strip the figures of their “national statistics” kitemark.

Until we can trust the way crime statistics are collated, there is little chance of restoring public faith in their veracity.

Crime fell by 10 per cent in

England and Wales in the year to 2013, according to figures released yesterday

by the Office for National Statistics. On the face of it that is excellent

news, confounding the predictions of those who said cuts in local police

budgets would see a rise in criminality.

But does anyone believe the figures any more? Public confidence has been

dented by recent revelations from police “whistleblowers” that the way forces

record crime has been flawed, though that is putting it kindly: fiddled, others

would call it. Indeed, the UK Statistics Authority has withdrawn its official

designation from all crime data recorded by the police.

Yesterday’s statistics, however, were based on the British Crime Survey

(BCS) of some 40,000 people, who are asked about their experiences over the

past 12 months. The BCS has consistently shown a decline in offending over the

past 20 years. Yet it is an unsatisfactory measure, since it excludes offences

involving the under-16s, the homeless, all businesses, murder, manslaughter and

so-called victimless crimes such as drug abuse. Having two sets of figures is

also confusing: once, the BCS was supposed to complement the police data, but

it has now become the main measurement of crime.

Arguably, the collection of national – as opposed to local – crime figures

is no longer worthwhile, if it ever was. As long ago as 1968, the Perks

Committee on Criminal Statistics proposed that the periodic deluge of

statistics should be replaced by an annual crime index, weighted to reflect the

relative seriousness of offences. This is a good idea; but such an index would

need to be based on police recorded figures – and until we can trust the way

they are collated, there is little chance of restoring public faith in their

veracity.